Henrietta Lacks lived from 1920 to 1951, but her cells are still around. Rebecca Skloot’s The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks is a personal and scientific history, keeping the focus away from a direct moral argument. In her telling of the personal effect on the Lacks and of Henrietta’s life, she treats the family’s stories very centrally. Skloot narrates the Lacks family’s concerns and beliefs about the case in terms of her interviews with them. She characterizes the family as wronged and still bitter, largely because they’ve been kept in the dark about what Henrietta’s cells were doing, how they had been taken (including the mere fact that they had been taken), or even what the cells were. She also includes a narrative about the breakthroughs that HeLa has helped with—developing this dilemma between the wrongs perpetrated against the Lacks with the wider benefits. The merging of the the personal and impersonal medical narratives lets the dichotomy exist without being exactly resolved. It also plays to much of the honoring of Henrietta’s memory—as her children and Skloot want to do, memorializing Lacks’s life and death.

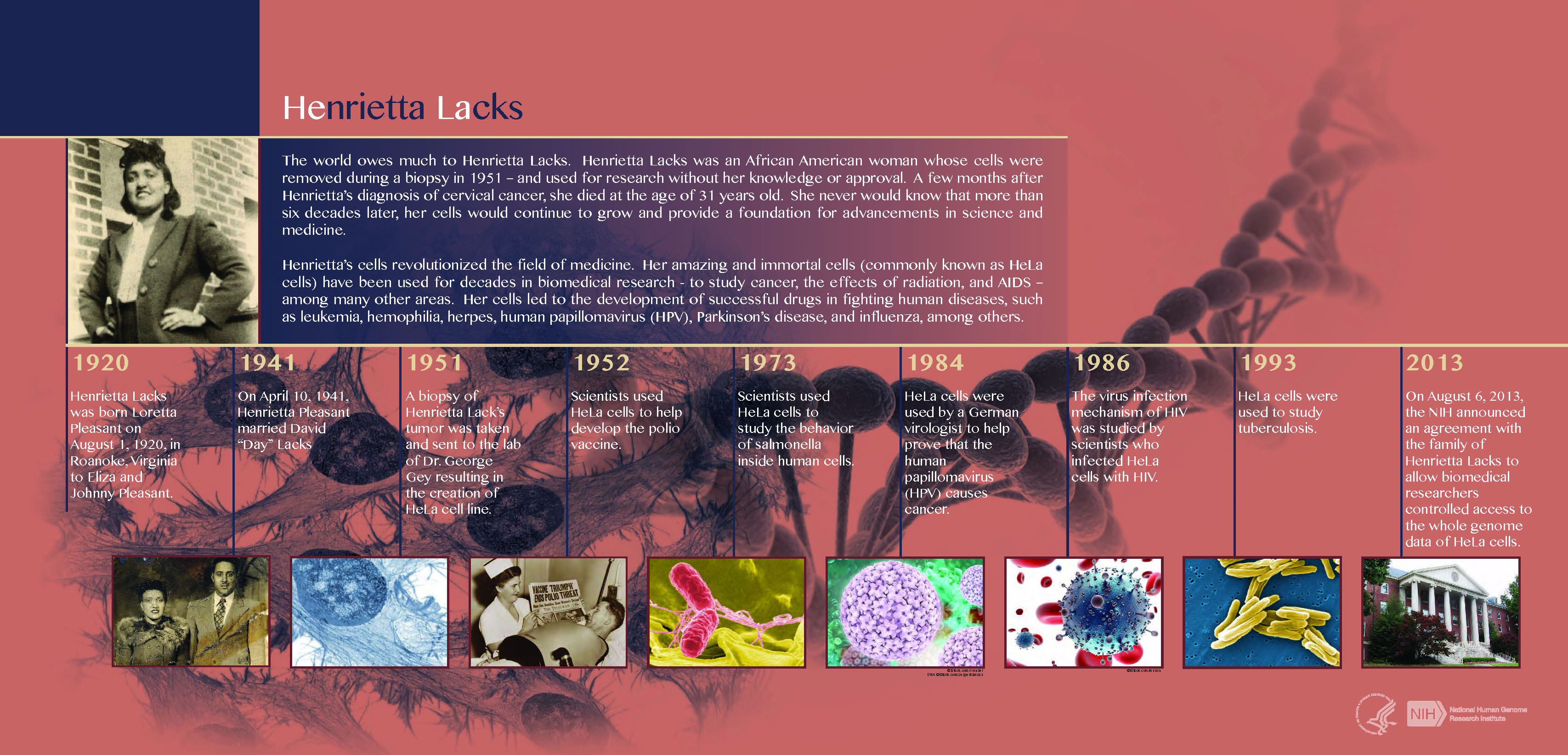

This timeline, on the other hand, is not a memorial to Henrietta’s life. It informs the viewer of Henrietta’s life’s milestones and the fact that she didn’t give consent to have her cells taken, but it doesn’t focus on that fact. The timeline is a medical history reference, so unlike the book or this Nature article, it does not focus on the morality of the situation or points of view from Henrietta’s family. Instead, it focuses on the scientific results, especially in the blurb above the chronological timeline. This shows a bias towards researchers and those achievements, so the authors more probably believe that the value derived from her cells should be celebrated.

The Nature article proposes that the practice of taking cells without consent (or doing other things) should be banned. It structures the argument around Henrietta’s personal story, using her innate rights to argue that patients like her (and by extension their families) deserve to have control over their cells. Its focus is on the opposite spectrum from the timeline, dampening the scientific achievements to highlight the ethical argument instead.