The Digital Millenium Copyright Act (DMCA) section 1201 makes the circumvention of Digital Rights Management (DRM) illegal, even when doing so wouldn’t violate any other copyright protection. The DMCA allows companies like Netflix and Amazon to punish piracy of the movies and television they stream, but, until recently, it let manufacturers like John Deere prohibit you from repairing your own device (like a tractor), and it lets medical device manufacturers like Medtronic prohibit you from testing their security or repair their ventilators without requiring an overpriced, unavailable Medtronic mechanic come type in a special code. It’s “felonizing contempt of business model,” as consumer advocate Cory Doctorow puts it.

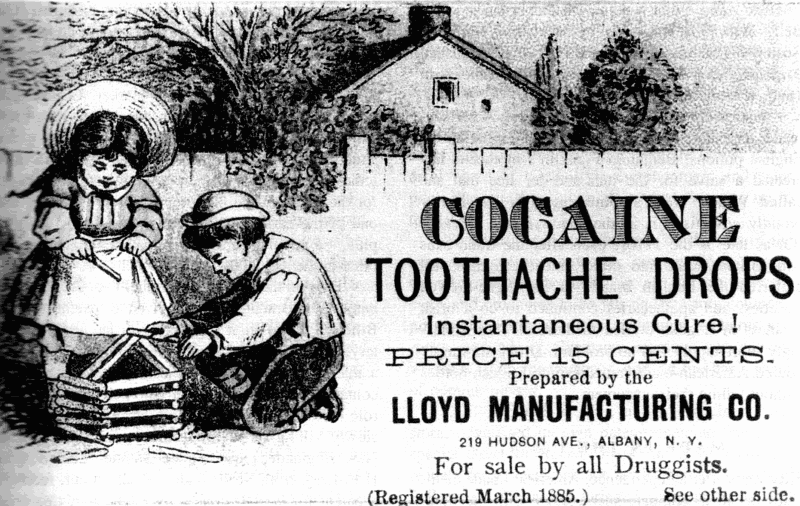

But these problems aren’t exclusive to the DMCA. The DMCA is just one way in which megacorps, often with monopoly or oligopoly status, maintain their profits—at the expense of customers. Insulin pumps, pacemakers, ventilators, and insulin, by nature of the market, have maintained the power of their originators over their users. Intellectual property, in the form of patents and copyright, and a political system that allows Super PAC lobbying and pay-for-delay is how corporations maintain their hegemony.

There is a fundamental issue with the way the current system is being run, and I want to look into that with the help of a medical device or high-cost drug. These are symptoms, and I think that I’ll be able to find evidence that, despite the good that research funneled through corporations has done, the system that rewards corporations so heavily is unjust.