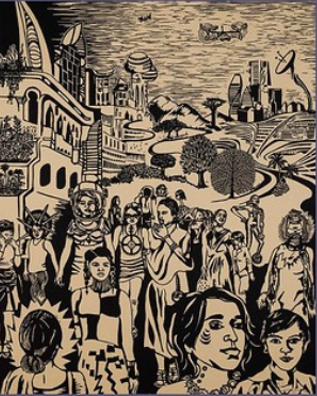

“When walking I found to my surprise that it was a fine morning. The town was fully awake and the streets alive with bustling crowds. I was feeling very shy, thinking I was walking in the street in broad daylight, but there was not a single man visible.”

This an excerpt from “Sultana’s Dream” – a sci-fi short story written in 1905 by a pioneering feminist in Bengal. Rokeya was born to an elite Muslim family where she had been loved, but expected of a ‘dignified’ life at home, behind the veil – “purdah”. She was allowed literacy, but with the sole purpose that she would read and abide by religious texts. As cliché as it sounds, Rokeya did defy the odds – not only through her protagonists, but also in real life. What influences, besides her innate curiosity and spirits, helped this young girl outgrow the norms that she was ingrained with, intrigues me. Rokeya arrived in the city at a time when it was in high spirits of political discourse – the British colonial rule was nearing its end with a plan to divide the subcontinent on a religious basis. Urban civic societies began to think on the pillars of a nation – what unifies people in a territory where allegiance to the motherland and allegiance to the traditions run parallelly like the banks of the river but never meet? The issue of feminism was complexly intertwined with freedom, religion, and culture. All this leads to a question:

Is Unrest Good?

Photo: Mahmud Hossain Opu

As the daughter of a feudal lord, Rokeya’s earliest observation was simple but deeply political. As they sat together to oil their long locks of hair in the female-only quarters known as zenana or andarmahal, she would listen to stories of abject poverty from the daughters and wives of the peasants. Growing up she also noticed the decline of self-reliant villages that produced sufficient clothing through handlooms run candidly by women as a side-gig. She saw a large part of society fall into dormancy and paralysis – the reasons of which became ever so clear when she understood politics, power dynamics, cultural clash and colonial policies.

The Break of Dawn

In our Bengali class, we had come across a difficult word – “অসূর্্যস্পশ্যা” (Aushurjosposshya). It was difficult to pronounce, to spell, and even to imagine – as it meant someone who had not been touched by the sun. It was a reality, nonetheless, for women across the rural-urban and religious landscape, the extent of which depended on lineage and communal values. Bengal saw its fair share of turbulence in the Modernist era amid which “the sun” was gradually redefined as the access to greater society – one that is socially, politically informed. The earliest Muslim women who received formal education would commute to schools in covered vans – the arrangement so private that I have not found a photo or rendition of it to date. Nevertheless, “Sakhawat Memorial Girls’ School” established by Begum Rokeya was up and running since 1909.

Going to school had larger implications than the obvious benefit of gaining literacy. The co-mingling of girls from different religious and social backgrounds for the first time was another step ahead in easing the boundaries that perpetuated among communities. An intergenerational change could be observed, even the older generations seemed to free up, albeit gradually – amid moral crisis. The commentary of Zainab Amin, a woman born in 1934 to a progressive Muslim family, about visiting a Hindu classmate’s house illustrates the situation:

“So when I went … I would naturally go and pay my respects. She (paternal grandmother)

would be very affectionate [Bheeshan adar korten]! But in their house,

I have never sat in their dining room and eaten together with … [the family]. I mean when in the drawing … room [bashar ghare] where

I was sitting, food was being served and everyone is eating … Ira is

eating, I too am eating.… But in their dining room, eating from the

same plate sitting next to each other … that commensality was not

[possible] in that family…. When she came to my house, if we are

eating [we would say] “Ai, aye ekhane bosh [Come sit here] … eat a

little with me.” That she would eat … but in their household it was

not possible. But I never felt bad about that … they are Brahmin.…

And yet, when after my marriage I took my husband to their house,

Ira’s thakuma [paternal grandmother] herself blessed him….” (Sarkar, p.14)

Hence, educational institutions had been playing salient roles in smoothening out cultural boundaries through new friendships and natural affiliations in a non-imposed, spontaneous manner.

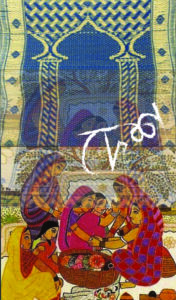

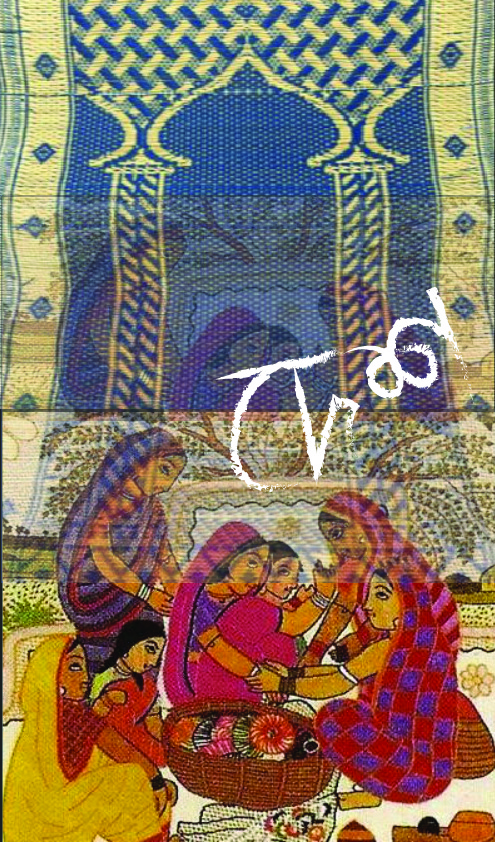

The cover image I made symbolizes the gist of the scholarly article “Changing Together, Changing Apart: Urban Muslim and Hindu Women in Pre-Partition Bengal” where the oral accounts of four women – two Hindus and two Muslims – of the first half of the twentieth century were analyzed. I combined two artifacts: a jaynamaz, an Islamic prayer mat, and a handicraft featuring women preparing for a Hindu puja. They seem to blend into each other, although with a distinct partition, by dint of modern education and nationalism – which I symbolize with a chalk-written word – “দেশ – desh” meaning “country”, which was of high significance as the fight against the colonial rule climaxed in the first half of the twentieth century.

The Transition Captured in the City’s Art

According to Ashit Paul, the curator of the “19th Century Swadeshi Art in Bengal Woodcuts, Woodblocks & Lithographs” exhibition, the lanes of Battala (the banayan shade) in north Kolkata was the birthplace of the Bengali printing presses in the early 19th century. He further comments, “Battala soon came to be associated with the sphere of literature exploring social scandals, with undertones of an intensely eroticized language.”

Erotica and literature on social scandals could be traced in Bengal long before the 19th century, however, the submissive and puritan woman narrative dominated those pieces. What was new about Battala, was a reversal of those narratives to certain extents. Brinda Bose, author of “Modernity, Globality, Sexuality, and the City” recollects the “Unreal City” described in “The Waste Land” and remarks :

It is clearly no passing coincidence that one of the most significant symbols of the degenerate modern city, sterile, mechanical, soulless as it is, is the sexually promiscuous woman – a recurrent sign used symbolically, metaphorically, and metonymically across cultures to signify a changed, if not deranged, landscape. What makes this signifier interesting, however, is not its apparent connotation of moral degeneracy but its simultaneous admission of a metamorphosed autonomy of the female self.

This evolving genre at Battala appears to me as an unintentional normalization of the brazen side of the feminine, which as Bose points out, is a significant symbol of the modern city, irrespective of how that is interpreted.

Gendering Urban Spaces

I animated a stylized map of Dhaka city by an Instagram artist @dhakayeah to portray the fact that women’s access to public spaces are limited to norms – the density of a place, the time of the day among others. Quoting Brinda Bose, “Urban spaces are in fact excellent sites for analyzing how gender works, in Bourdieu’s terms, as an “embodied idea,” suggesting that spatial divisions within the city – the street, the office, the kitchen, the bedroom – are not always gendered in obvious or given ways, but enacted through embodied practices.“ (Bose, p.41)

This connects back to “Sultana’s Dream” where the notion of gendered spaces is addressed as well. The picture here though is rather contemporary. In “Sultana’s Dream” there are no manually-pulled rickshaws with male drivers. Public transport in Rokeya’s Ladyland is coordinated by women. The gendered space in Ladyland is a satire, a “terrible revenge” as Rokeya’s husband appreciated, of the status-quo blind to the oppressive segregation. The landscape of Ladyland may come off as superfluous female-supremacy, especially now that the discourse of gender equity has been established. However, back in the time, this is the shocking, avant-garde contrast that was required to shake things up – an alternative reality that challenges every single pillar of the urban society.

25 years after writing about the aircraft in her story, in 1930, Rokeya had for the first time seen the vehicle and subsequently toured on it around Calcutta. She journaled the experience and absorbed that the first Bengali Muslim female pilot had flown a Muslim woman in purdah (Rokeya) for the first time.

Despite such milestones, the cities of Bengal in the 21st century are not female-friendly spaces.1 Misogynistic and heteronormative mindset exists in the greater population. The conclusion of my research analysis recognizes the impact of cities on feminist discourses in twentieth-century Bengal, however, the voice of emancipation that drove these discourses is not linearly rooted in urbanization, rather in a humanitarian awakening raged through prolonged servitude. Unrest, be it material or spiritual, has been the harbinger of change, although the change is actually rooted in collective consciousness. Over time, the collective consciousness wears off amid the crushing pressure of urban existence, the voice of change tends to get muffled amid the noise. The city is notoriously known for culturing the noise which is why “Sultana’s Dream” is still relevant.

Works Cited:

Hossain, Rokeya Sakhawat.”Sultana’s Dream”. The Indian Ladies’ Magazine, Madras, 1905

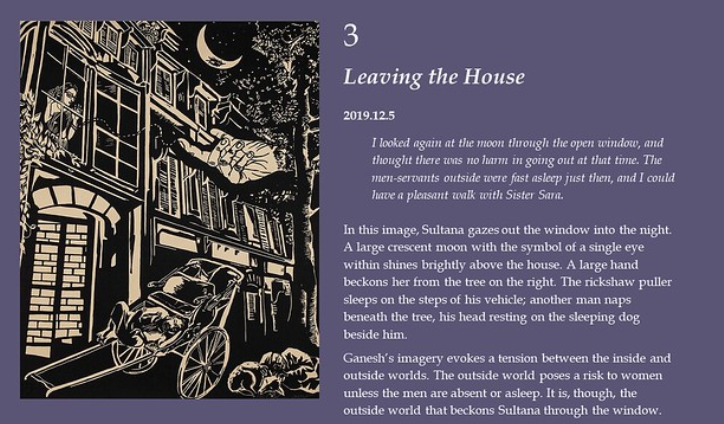

Ganesh, Chitra. “Sultana’s Dream: Digital Edition”. Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester, 2019

Sultana’s Dream: Digital Edition | Flickr

Sarkar, Mahua. “Changing Together, Changing Apart: Urban Muslim and Hindu Women in Pre-Partition Bengal.” History and Memory, vol. 27, no. 1, 2015, pp. 5–42. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.2979/histmemo.27.1.5. Accessed 28 Feb. 2021.

Bose, Brinda. “Modernity, Globality, Sexuality, and the City: A Reading of Indian Cinema.” The Global South, vol. 2, no. 1, 2008, pp. 35–58. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40339281. Accessed 28 Feb. 2021.

DhakaYeah. “Give the gift of Dhaka, this holiday season.” Instagram, Nov 7, 2020

https://www.instagram.com/p/CIGS2X-JMBS/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link

Das, Priyagopal. “Adbhut Hatyakanda” (1914). P.M. Bagchi and Co; 19th Century Swadeshi Art in Bengal Woodcuts, Woodblocks & Lithographs. Ashit Paul

Reference:

- Kotikula, Andy and Diana J. Arango. “Walking the street with DIGNITY: Women’s inclusion in urban Bangladesh.” World Bank Blogs. Dec 10, 2019

Walking the street with DIGNITY: Women’s inclusion in urban Bangladesh (worldbank.org)

I think you did a really great job with this essay. It was really interesting to read about feminism in a non western context, as most of the history I’ve learned about has been North American or from Britain. The explanation of the word “ ‘অসূর্্যস্পশ্যা’ (Aushurjosposshya)” was beautiful and it was super descriptive of the kind of box women have and still are put in Bengal.

The animated map also demonstrates really clearly the relationship between women’s oppression and access to certain spaces at certain times. I like how it’s a sort of dark wave that encloses everything and it looks very cool and eye catching.

Also the quote concerning reversing women roles in literature and the relation with this and the city was super enlightening and made me think about how the city is often negatively represented through the image and metaphor of a promiscuous woman. I never picked up on this but thinking about pop music and movies, it’s really obvious and would be interesting to further explore.

Your last sentence, “The city is notoriously known for culturing the noise which is why “Sultana’s Dream” is still relevant.” was a great way to tie everything back together and made me reflect on the thin lines between crushing urbanization and consciousness that leads to positive change.