Kaylin Belwood, ENGL 1102 – 11:00

Los Angeles is a city that everyone knows of, but few know anything beyond its existence. To outsiders, the city is often associated with celebrities and the rich; Rodeo Drive in Beverly Hills is packed with designer brands, and Hollywood houses some iconic architecture, including Grauman’s Chinese Theater and the Hollywood Sign. However, many people tend to forget that LA is just like any other city; working class citizens struggle to make a living while paying extraordinarily high rent. The city is a culturally rich area with large minority populations. California was Spanish territory in the early 1800s, and many Chinese and other Asian immigrants travelled to Angel Island and settled in California during the Gold Rush. During the Second Great Migration, many black Americans travelled from the segregated South to California. Because Los Angeles has been a large cosmopolitan area since it was built, the different ethnic communities have frequently clashed, leading to several riots in Los Angeles history, including the Zoot Suit Riots, Watts Riots, and Rodney King Riots. Several rock and metal groups used their music to protest racism perpetuated by the police department in Los Angeles in the 1990s following the Rodney King Riots.

Los Angeles and the surrounding areas have large enclaves with populations from around the globe; Chinatown and Koreatown represent some of the Asian populations settled in LA, and Mexicans and El Salvadorans make up a large percentage of the Latino population. Because Los Angeles held large populations of minorities, cultural clashes were inevitable. In 1943, the Zoot Suit Riots were a series of altercations between American servicemen and Mexican American youths living in Los Angeles. A zoot suit is a men’s suit characterized by wide-legged trousers and long coats. The outfits were criticized during World War II since the suits require copious amounts of fabric, which many considered “wasteful” since fabric was rationed. Zoot suit wearers, often Latino, were targeted and attacked in Los Angeles. Several modernists artworks, specifically from the futurist movement, depict a similar tension in growing industrial cities. The City Rises by Umberto Boccioni explicitly shows conflict between draft horses and pedestrians on the streets of a rising city. However, the tension Boccioni depicts can be related to the cultural and racial tensions in Los Angeles that still exist to this day; in relation to the Zoot Suit Riots, the horses depict the servicemen as they attack Mexican American youths wearing zoot suits. Umberto Boccioni painted another piece called The Street Enters the House that depicts a bustling street as a man looks on. Much like the people in the painting, many living in Los Angeles just wanted to carry on with their lives and did not search for fights with people of other cultures. Clashes were infrequent, but several cases have caused huge riots where people were seriously injured and even killed. Another futurist artwork, The Funeral of the Anarchist Galli by Carlo Carrà, depicts an actual fight between anarchists and police during a funeral procession; similarly, rioters and police clashed in Los Angeles during the Watts Riots, a series of riots that followed the beating of a black man and his mother resisting arrest, and the Rodney King Riots. Rising tensions between minorities and the Los Angeles Police Department led to a series of violent conflicts now known as the Rodney King Riots.

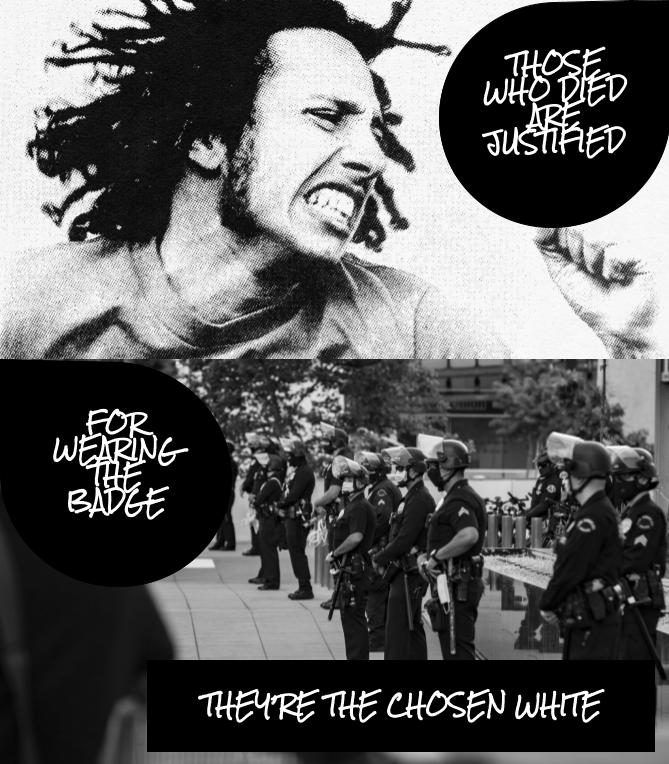

Rap-metal band Rage Against the Machine has long used their music as a tool of protest. In 1991, activist Rodney King was brutally beaten by Los Angeles police during his arrest for a DUI; the officers that beat him were acquitted by an all-white jury in 1992, sparking the infamous Rodney King Riots, also known as the LA Riots. Following the riots, the song “Killing in the Name” was released in November 1992. Written by singer Zack de la Rocha and guitarist Tom Morello, the song was intended to be a fight against brutality and corruption in the LAPD. As producer Garth Richardson recalled, “Zack and I had a long talk about the power of speech and how whatever he needed to say, he had to say it. Malcolm X was a major influence in Zack’s life, and this was not the time to back down.” Richardson produced Rage Against the Machine’s first album, Rage Against the Machine, which included the single “Killing in the Name.” Several lines within the song directly call out the corruption often associated with the Los Angeles Police Department in the 1990s. For example, one repeated mantra within the song states, “Some of those that work forces are the same that burn crosses.” In this line, de la Rocha and Morello compare the blatant racism of the Ku Klux Klan to the racist actions perpetuated by the LAPD. Cross burning was used by the KKK to instill fear in black Americans in the mid-1900s; many people saw the brutality of the LAPD as another fear tactic that targeted vulnerable populations. Another line in the song references the officers’ trial and claims “You justify those that died. By wearing the badge, they’re the chosen whites.” De la Rocha and Morello feel that the police were acquitted in the trial solely because they were police; the police were trusted by many, so deaths at the hands of these officers were thought to be “justified.” The image below is a collage depicting Zack de la Rocha and a group of riot police with some lyrics from “Killing in the Name.” De la Rocha’s facial expression is so powerful and emotional compared to the calm nature of the police in the picture shown; during this period of unrest, many were enraged by the inaction of the police department to hold their officers accountable for despicable acts. The calm of the police depicts the complacency within the LAPD while de la Rocha channels the emotions of the masses into his music.

The song “LAPD” by The Offspring, much like “Killing in the Name,” focuses on the issues within the Los Angeles Police Department in the 1990s. In the first verse, vocalist Dexter Holland sings, “When cops are taking care of business I can understand, but the L.A. story’s gone way out of hand. Their acts of aggression, they say they’re justified…” Similar to the line sung by de la Rocha, Holland wants to show that Los Angeles police officers believe they are in the right simply because they are police officers. The police can beat and abuse almost anyone with the justification that they are the law. In the next verse, the line “Take it to a jury but they don’t give a damn” may be a direct reference to the trials of the four LAPD officers that participated in Rodney King’s beating. Despite video evidence of the officers senselessly beating King during his arrest, all four were acquitted by the jury. Near the end of the song, Holland sings, “They say they’re keeping the peace, but I’m not buying it because a billy club ain’t much of a pacifier.” Holland felt that the police incited more unrest by beating rioters; peace can not be kept unless both sides are abiding. By fighting violence with violence, the police caused greater uproar among protestors. At the very end of the song, Holland yells, “Law and order doesn’t really matter when you’re the one getting bruised and battered. You take it to a jury, they’ll throw it in your face because justice in L.A. comes in a can of mace.” Much like the line stating that the jury doesn’t “give a damn,” the band wants the audience to realize that the police are not on the people’s side. The last phrase of that quote could be interpreted as explaining that justice in Los Angeles is based on self-defense rather than through the law. The Offspring wanted to use their privilege to bring awareness and justice to the Rodney King beating.

Reggae rock and ska punk band Sublime released the song “April 29, 1992 (Miami)” in July 1996. On April 29, 1992, the four officers charged with Rodney King’s beating were acquitted by an all-white jury. Writer and music critic Ian Port explains, “… the song is about the L.A. Riots: Specifically about Sublime members’ alleged involvement in the looting, burning, and general hell-raising that took place in the streets…” While the lyrics of “Killing in the Name” focus on the reasoning behind the riots and those of “LAPD” focus on corruption within the police department, “April 29, 1992 (Miami) focuses on the events of the riots. The lyrics shift between singer Bradley Nowell and a police dispatch. In the first verse of the song, Nowell sings about looting and destroying a liquor store and a music shop. Despite being part of the Rodney King Riots, Nowell looted for his own benefit, stealing alcohol and a guitar. Later in the song, Nowell sings, “They said it was for the black man, they said it was for the Mexican, and not for the white man, but if you look at the streets, it wasn’t about Rodney King.” Much like the riots that occurred following George Floyd’s death, many people joined in the riots solely to loot or cause chaos. However, those who protested truly felt that the Rodney King situation was a tipping point in the struggle against the LAPD. Although Nowell admits to using the riots as an excuse for personal gain, he also recognizes the integral role the riots played in the correction of the LAPD and its corruption.

Music has long been a form of protest, and rock and metal musicians are still using their voices to encourage and demand change in society. In the aftermath of the George Floyd protests and riots in 2020, bands like Bon Jovi and Machine Head released songs that discuss the abuse of power and racism within law enforcement. Even though the Rodney King riots took place nearly thirty years ago, citizens are still protesting the way the police treat black Americans across the country.

Works Cited

Boccioni, Umberto. The City Rises. 1910, Museum of Modern Art, New York City.

Boccioni, Umberto. The Street Enters the House. 1911, Sprengel Museum, Hanover.

Carrà, Carlo. The Funeral of the Anarchist Galli. 1911, Museum of Modern Art, New York City.

Hughes, Rob. “Story Behind the Song: Killing in the Name by Rage Against the Machine.” Louder, 12 February 2019, https://www.loudersound.com/features/story-behind-the-song-killing-in-the-name-by-rage-against-the-machine. Accessed 21 February 2021.

Port, Ian S. “Twenty Years Later, Sublime’s ‘April 29, 1992 (Miami)’ Is Still the Best Song About White Boys Piggy-Backing on a Riot.” SF Weekly, 26 April 2012, https://www.sfweekly.com/music/twenty-years-later-sublimes-april-29-1992-miami-is-still-the-best-song-about-white-boys-piggy-backing-on-a-riot/. Accessed 26 February 2021.

Rage Against the Machine. “Killing in the Name.” Rage Against the Machine, 1992.

Sublime. “April 29, 1992 (Miami).” Sublime, 1996.

The Offspring. “LAPD.” Ignition, 1992.

Wow this was really interesting to read! I found it really insightful how you not only discussed music as a means of activism, but connected it to a specific city and issue. Your juxtaposition of the glamour of Hollywood and the social and economic hardship of life in LA really helped contextualize what the argument is about and was a good hook in. The modernist images you chose are very apt in describing the mental space you are discussing. I especially liked “The Funeral of the Anarchist” in this context – you images really contribute actively to your argument. Connecting you argument to current events was also very helpful in this regard. If I had to offer criticism, I would have been interested to read more on the reception and social response to the music you discuss. How did this music influence movements and the state of the world today? Overall this was incredibly comprehensive and engaging and it’s motivated me to go listen to some of these songs.