Jack Edge – 9:30 Class

If someone asked you if Atlanta is a modern city, what would you say? You might point to modern amenities like 5G, 24/7 donut shops, access to running water, and same-day Amazon delivery. Now consider the same question, but with “modern” referring to the archetypal modern city of the early 20th century. At that point, you might not even understand the question, but you’d know for sure that Atlanta isn’t that, if only for the fact that it is the year 2021, not 1921. However, Atlanta today has more than a few things in common with the crowded industrial cities of a century ago.

Now, what if someone asked you what the greatest recurring problem facing Atlanta is, what would you say then? You might say crime, owing to Atlanta’s perception as an aggressive, firearm-heavy city. While crime is high in Atlanta, many long-term residents might point to gentrification. Now, the word “gentrification” has the potential to mean different things depending on who you ask. To some, gentrification means the transformation of a low class, run-down area into a higher class area with improved infrastructure and living conditions. To others, it is an “-ation” that encompasses a loss of community, livelihood, and culture. In reality, gentrification involves both of these changes to an area, as shown by its definition as well as by a stroll through an area that has been affected by gentrification. Many Atlanta residents can tell you the anecdote about their house’s property value increasing five-fold in the past decade. This gentrification is a result of many initiatives in the last few decades, from tougher (but no less racist) policing mirroring that of other U.S. cities in an effort to break Atlanta’s long reputation for being dangerous, to the Atlanta BeltLine initiative, which was created by Georgia Tech student Ryan Gravel to build a sightseeing path around the city of Atlanta. Both Gravel and CEO Paul Morris resigned due to controversy over soaring housing prices near the BeltLine and failure to build promised affordable housing.

Initiatives like the BeltLine have caused Atlanta to become a lucrative city for both businesses and upper-middle class families with a bit too much disposable income to relocate to. Gentrification and crime go hand-in-hand, and both issues are part of the broader issue of wealth inequality. While gentrification of an area may appear to reduce crime, it usually only moves the issue somewhere else. For perspective, here’s some data on wealth inequality in Atlanta. In 2019, the top 5% of Atlanta households made 10.7 times more income than the bottom 50%, making Atlanta the city with the highest wealth inequality in the U.S. Atlanta, as home to Coca-Cola, Delta Airlines, UPS, and many other Fortune-ranked corporations is also infamous for its many “hoods” where living conditions and income are poor and crime is rampant.

As for the elephant, or rather, the yellow jacket in the room (I’m so very sorry), Georgia Tech does stand out in comparison to many surrounding areas. In its expansion westward in the 1960s, the African-American neighborhood of Hemphill was razed, and the 1996 Olympic Games caused further expansion of campus outward. Georgia Tech’s current campus is a product of gentrification. That said, there’s a lot more to Atlanta than Georgia Tech.

One aspect that has divided Atlanta on racial and wealth grounds is car culture. Not only was downtown Atlanta’s interstate highway system deliberately built to mark the boundaries between black and white neighborhoods, it has also drawn a superficial distinction between the classes. “Only poor people ride the MARTA.”

Something that has long been associated with areas of low income is graffiti, of which Atlanta is not lacking in. Graffiti has long been viewed as both a nuisance and a perfectly valid means of artistic expression, depending on who you ask. Graffiti in many ways could be considered an avant-garde artistic movement, as it is often misunderstood, born out of discontent, experimental, and challenging to authority. However, in recent years, graffiti-style art, usually in the form of official commissioned wall murals, has become an increasingly common sight in many cities looking to rebrand, with Atlanta as no exception. Many businesses and local governments have commissioned or sanctioned these murals, which are usually “clean” (no willies here) and unchallenging to authority, in an effort to appear “cool” and liven up the atmosphere of an area.

You may have noticed that I haven’t said anything about Modernism yet. Indeed, what does wealth inequality in Atlanta today have to do with modernism?

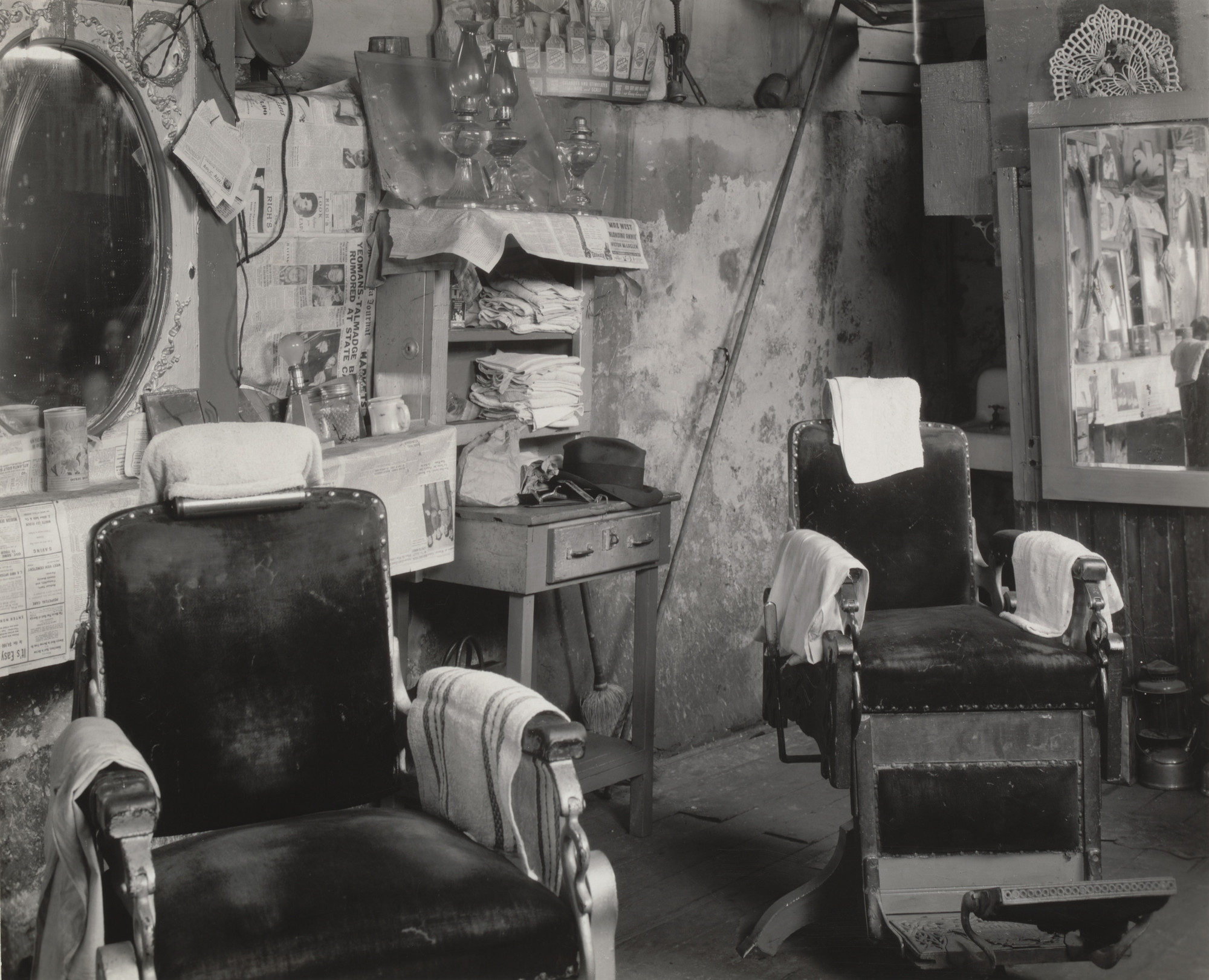

The transformation of the world (or at least the western world) in the Modernist era, prompted in part by the Second Industrial Revolution, involved the influx of people into the industrial and business-centered cities that contained job opportunities that could not be found in rural areas. These modern cities were crowded owing to the high population density and they were often ridden with crime owing to low wages and poor living conditions. Wealth inequality was blatant, with industrialists like Rockefeller, whose Standard Oil reigned as a monopoly well into the Modern era (it was broken up during the presidency of Taft, also known as the “bathtub sticker”), earning massive amounts of wealth off of the labor of workers making almost nothing. These cities were divided physically based on wealth, with workers living in inner-city slums and those who could afford to living in a different part or away from the city altogether.

The problems of the modern city led to several avant-garde artistic movements that challenged, parodied, or glorified the modern city, which were collectively known as “Modernist” movements. These movements often provoked the ire of the general populace and authorities for pushing the envelope of acceptable conduct and subjects. However, they gained popularity both in sectors of the working class for raising attention to their plight and in the upper classes as a symbol of progress. Modernist architectural styles were in many ways a stark departure from architecture of the preceding Victorian era, but over time they became the preferred styles of new buildings.

By the middle of the 20th century, many of the ideas and styles developed in the Modernist era had made their way into the status quo. At the same time, however, cities continued to grow uninhibited, wealth inequality remained an issue, and many of the issues Modernist artists attempted to bring to the public’s attention were ignored. In a way, this paradox was the result of those with power as well as society as a whole taking only the favorable parts of the Modernist movement. The businessmen and aristocrats of the era may have taken a liking to Picasso’s Cubist masterpieces and the International style of architecture, but they preferred to ignore the “radical” Modernist thinkers that challenged their authority (especially feminists and early civil rights activists). This situation is characteristically similar to the one facing Atlanta today, where only certain parts of low income African-American culture are deemed acceptable to appear on the sides of buildings in rich neighborhoods or heard playing over a television advert.

With all of this considered, Atlanta, in its current state of growing wealth but stagnating justice, is a spitting image of the archetypal modern city as depicted in the works of Modernist artists and authors. The crowds of people may have been replaced by crowds of cars in traffic jams and sanctioned graffiti and clean rap beats over insurance commercials may have replaced avant-garde art movements, but Atlanta and many other cities across the United States have striking similarities to the dirty and broken cities of the Modernist era.

Works Cited

https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/gentrification

https://atlanta.curbed.com/2016/9/27/13070520/ryan-gravel-beltline-resigns-affordable-housing

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/08/14/magazine/traffic-atlanta-segregation.html