As the shockwave evolves, I watch destruction reign over the city. Instantaneous chaos. Hundreds of deaths, thousands of injured and three hundred thousand homeless. The city that raised me, I now watch it burn through millions of OLED pixels on a flatscreen TV in the heart of Atlanta. Paralyzed, helpless, desperate, I read it burn through the uncontrollable flow of messages on my phone. Destruction… Always precedes creation. For the fallen martyrs, we need to rebuild Beirut, the Switzerland of the Middle East. Beirut, a capital of art, innovation, culture and history. In this article, I will take you on a journey to discover the capital of Lebanon under a new perspective; that of a modernist poem.

We can define modernism as the transformation or metamorphosis associated with the creation of new forms of art, philosophy and social organization from the 1890s until the 1930s. Particularly, a modernist poem should embody this revolution while also taking the past into consideration. In fact, according to T.S. Eliot in Tradition and the Individual Talent (1919), “not only the best, but the most individual parts of [a poet’s work] may be those in which the dead poets, his ancestors, assert their immortality most vigorously.“ Through our three stops in our journey: history, demographics and revolution, we will be discovering the modernist poem that is Beirut.

First and foremost, the Lebanese capital bears witness to a dual modernist imprint engraved in each street, alley and wall. This dual imprint, as its name suggests, can be broken down to two main components: the history of the city and its cultural modernist heritage.

During its five-thousand-year history, Beirut was destroyed and rebuilt a total of seven times – neither counting the August 2020 blast nor the 1975-1990 civil war! From the Phoenician, Hellenistic and Roman periods, to the Middle Ages, Ottoman Rule and French Mandate, if Beirut has been able to survive, it is by adapting to each period and preserving important aspects of the past.

As the pictures above show it, a casual walk at downtown Beirut can turn into an archaeological expedition if you do not pay attention to where you are going! In fact, you could come across the Canaanite city wall, Crusader fortress walls, Iron Age shaft tombs, a Roman law school (oldest in the world!), Roman baths and many more archaeological sites. Each time Beirut was rebuilt, it was by using its past foundations.

This story alone is the epitome of what modernism represents: creating by using what has already been built in the past, always remembering our predecessors, but also always innovating. An osmosis between the past and the present can similarly be identified in both modernist poems and the city of Beirut. In art – and especially poetry –, the coexistence and synergy of different times was first introduced by T.S. Eliot in Tradition and the Individual Talent (1919) as a necessary element for innovation and creativity. Similarly, wouldn’t a city where skyscrapers and modern buildings rise over vestiges appeal to you?

At least it attracted models, billionaires and politicians from all around the world and served as a source of inspiration for many artists.

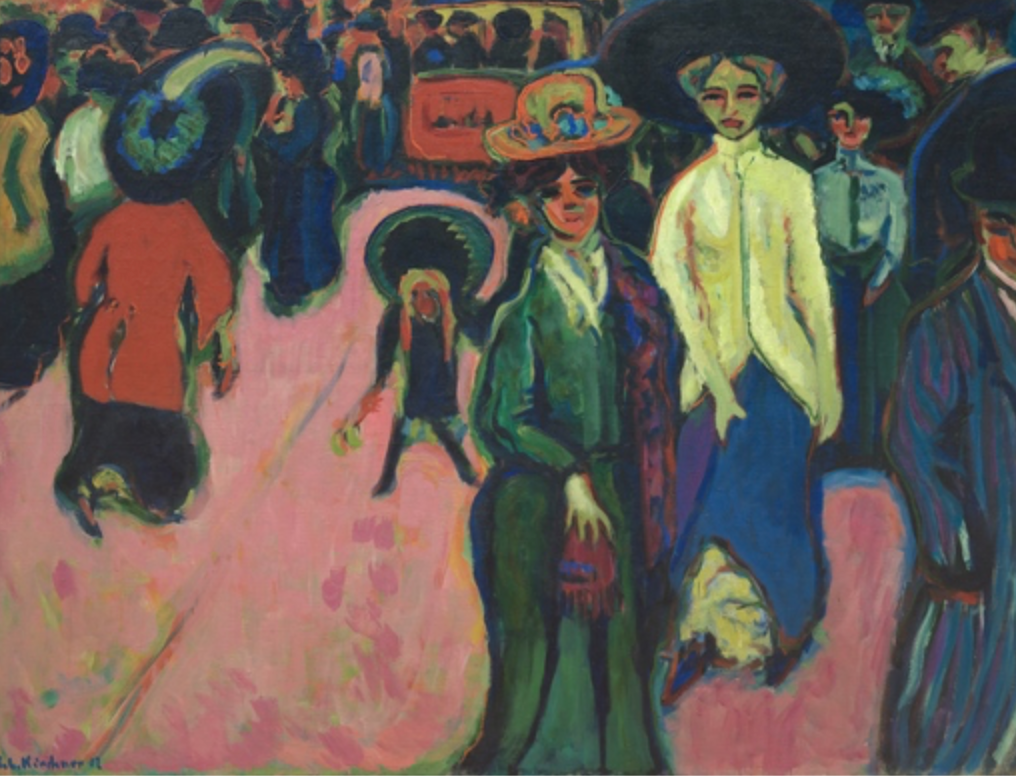

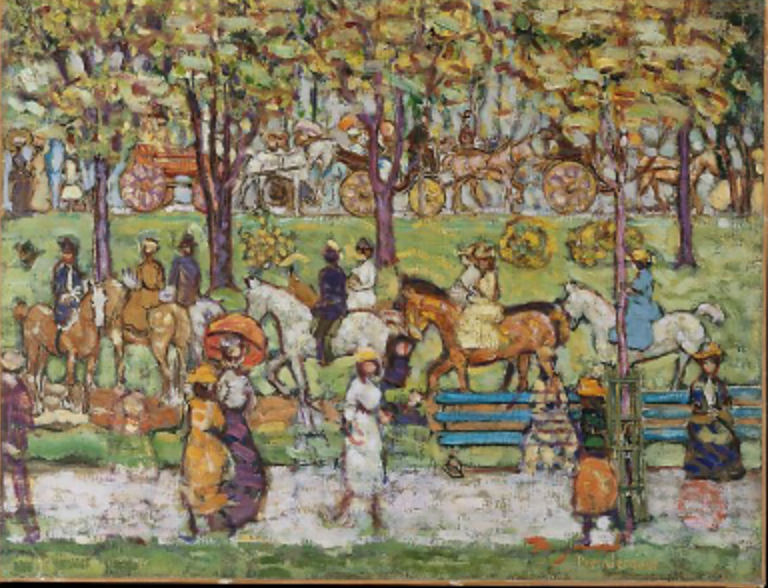

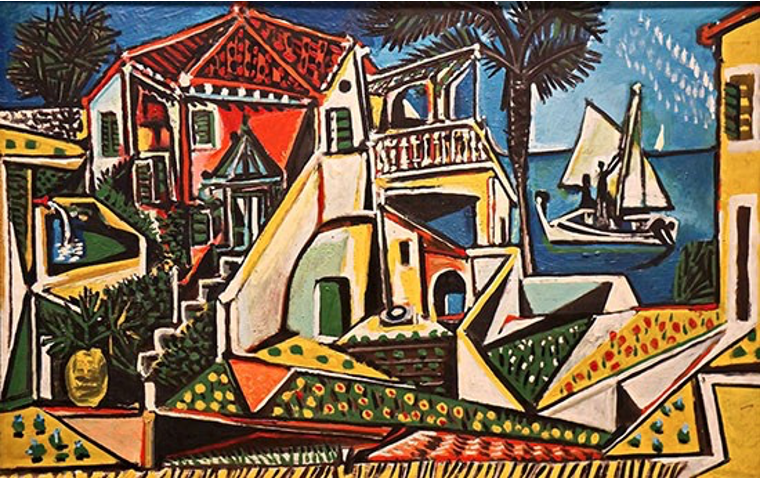

If in his painting Mediterranean Landscape (1953), Pablo Picasso did not specifically paint the shores of Beirut and Lebanon, this typical Mediterranean littoral, as much as any other Mediterranean city, depicts Beirut in all its diversity. At a first glance, the density of colors in the painting is striking, reminding us of the exotic, diverse, sometimes overwhelming Mediterranean lifestyle. We are also impressed, almost scared by the brutality of strokes, sharpness of angles and vibrance of colors characteristic of cubism, reminding us of the fierce History of this sea and Beirut. If international artists contribute to the cultural modernist heritage of Beirut, a blooming generation of local artists establish it. From Cesar Gemayel, Omar Onsi and Saloua Choucair, to Gibran Khalil Gibran, Fairuz and Mustafa Farroukh. Out of all the paintings by Lebanese modernists that I found, Daoud Corm’s Melons (1899) is the only one that truly affected me.

If you’ve never been to Lebanon, you need to know that we end every meal with a table of fruits. On the face of it, the painting appears relatively simple. However, the choice of colors alone triggered in me a complex mix of melancholy and peace: I could almost smell the usual Sunday lunch, feel the humidity of the atmosphere… And the knives! The cold silver knives typical of a Lebanese family, those centenary knives we still use and that those after us will also use, a symbol of how life is ephemeral. Maybe a symbol of how deep Lebanese are attached to their roots.

Demonstrating that Beirut is a capital of art during the modernist period is not sufficient to prove that this city is in itself a modernist piece of art. In order to do so, we need to dive deeper into the Lebanese demographics and lifestyle to verify if those factors truly embody modernism.

As we defined it earlier, modernism is the collection of artistic currents that saw the light from the 1890s until the 1930s. No matter how different those currents might be, like cubism that we saw earlier and post-impressionism that focuses on extending the limitations of impressionism by using new stroke techniques, all those movements belong to one family: modernism.

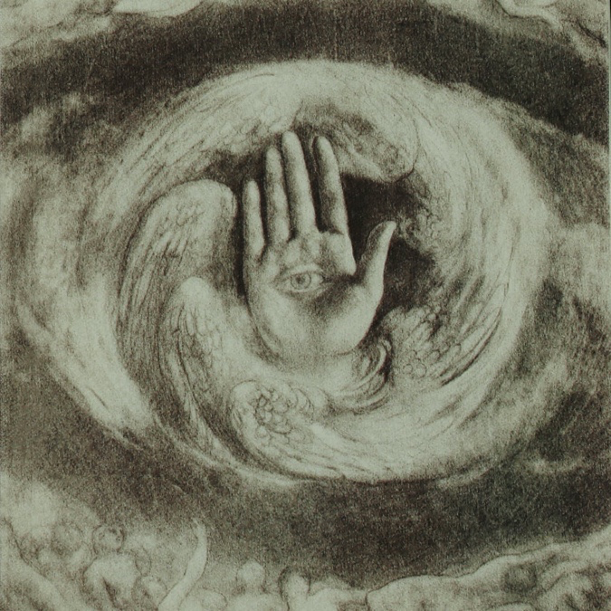

In parallel, Beirut is the collection of all different religions living in one city, a melting pot asserting the spirituality of the Lebanese. In the Divine World, what strikes us first is the Hamza at the center of the painting: an ancient Middle Eastern talisman, protective symbol in all religions. This symbol carries a powerful message of unity, setting all religions on an equal footing. If in Western modernism we witness a loss of God established by the rise of philosophical movements, notably the nihilism of Nietzsche: “God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him.”, Lebanese modernism distinguishes itself in its embrace and continued valuation of religion. Today, because religion brings back memories from the civil war, a horrendous period of Lebanese history, the unity of the people is stronger than ever regarding this matter.

The spirituality of the Lebanese is also particularly reflected in their approach towards life in general: a lack of material concern when it comes to education, helping others or living and enjoying life. Incorporated in the doctrine of many modernist poets – as Francis Ponge in Le Parti Pris des Choses – the Carpe Diem upon which the Lebanese live exhibits this deep spirituality they have. If the Carpe Diem urges us to make the most of the present time and give little thought to the future, enjoy life as we can, it is because memento mori, remember that you have to die. As the “collage” below manifests it, the Lebanese people do not fail at this task. The contrast in the variety of activities we can do in 24 hours may shock you, but as you can see, we do ski, waterski and party in the same day.

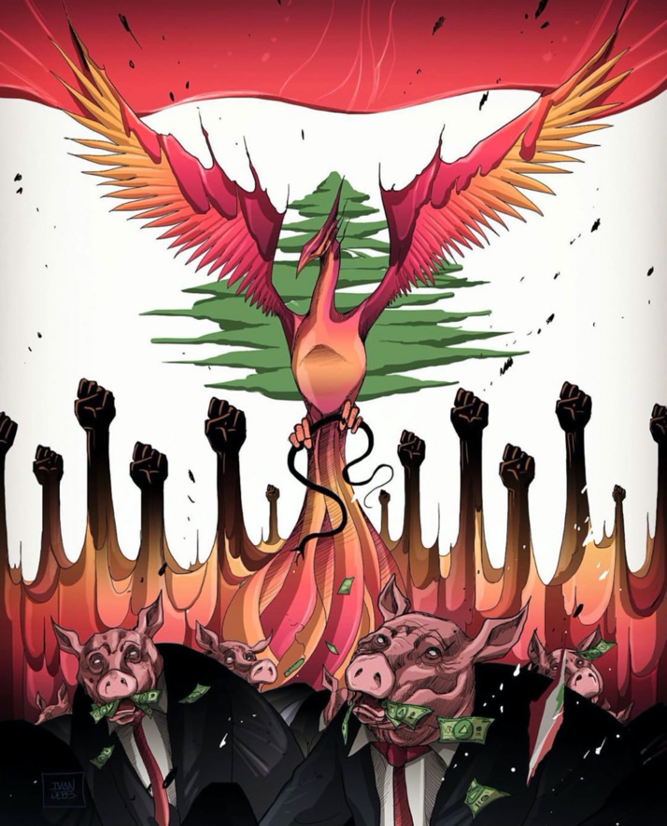

I have introduced you to a utopic city and country. I wish this is how Beirut was. You have probably seen her real face on the news. Oppressed, perverted, abused by a mafia of corrupt politicians, the fetid Beirut. However, similarly to the diamond that only forms under pressure, it wasn’t until the Lebanese were truly pushed to their limits that their philosophy really crystallized.

Tired of following the same leaders who get richer by stealing from them, Thursday October 17th, 2019, the people decide that things need to change. Not only is this a political or economic revolution, but a total revolution, a revolution of culture and society, a revolution of thought that unveils a new modernist face of Beirut. If modernism witnesses the questioning of higher authorities and the power associated with them, as in the character of Stephen Dedalus in James Joyce’s Ulysses, Beirut can be considered part of this movement insofar as the revolution of thought it lives is in itself modernist. The unity of the people against power and corruption on one hand manifests their spiritual unity – Beirut is a melting pot, a collection of different religions coexisting – and on the other attests the revolution of thought they have initiated, characteristic of modernism.

In parallel to the revolution, the financial crisis that hit the country finished of poleaxing the people, and of course, the poorest were hit the hardest. Try to predict what happened next. If you base your reasoning on Hobbes’ theory on social contract, the Lebanese people, deprived of their most basic rights, therefore considered in their “natural state”, with no social contract (or society) to guarantee them safety and benefit, are fundamentally “bad”, and we should observe a chaotic deterioration of the situation. In fact, according to Hobbes, “L’Homme est un loup pour l’Homme” or Man is a wolf to Man, and society tames us. However, what we observe is completely different: as the people suffered on the streets, more and more Lebanese NGOs and initiatives rose to help those in need, which is closer to Rousseau’s view on the matter: “L’homme naît bon, c’est la société qui le corrompt” or Man is born good, society corrupts him. Shedding light on the true state of nature of Man, the Lebanese revolution is truly a total revolution embodying modernist concepts.

All in all, from its violent history as the command post of many civilizations, to its diverse demographics and the Revolution it is going through, we can say Beirut is built similarly to a modernist poem. However, on some aspects the city is still anchored in the past and it is clear that its roots are strangling it. Some people still believe in the politicians that have the power since the civil war (1975-1990) while others are starving on the streets. Will Beirut rise from the ashes an eighth time?

References

The Nature of Things, Francis Ponge (1942)

Ulysses, James Joyce (1922)

Tradition and the Individual Talent, T.S. Eliot (1919)

Leviathan, Thomas Hobbes (1651)

The Social Contract, Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1762)