“CELEBRATE SPRINGTIME IN SAVANNAH!”

shouts the Official Savannah Website in proper serif letters, backed by a charming crisp photo of morning glories. “Savannah, Georgia is a charming Southern escape where art, period architecture, trendy boutiques and ghost stories are all set under a veil of Spanish moss.” The website then assures its adventurous audience, who hasn’t yet been swayed by the perky graphics, that there are “over 15 Can’t Miss” things to do in savannah. There’s a stroll on the waterfront, a shopping spree on Broughton street downtown and even a ghost tour, “if that’s your idea of a good time.”

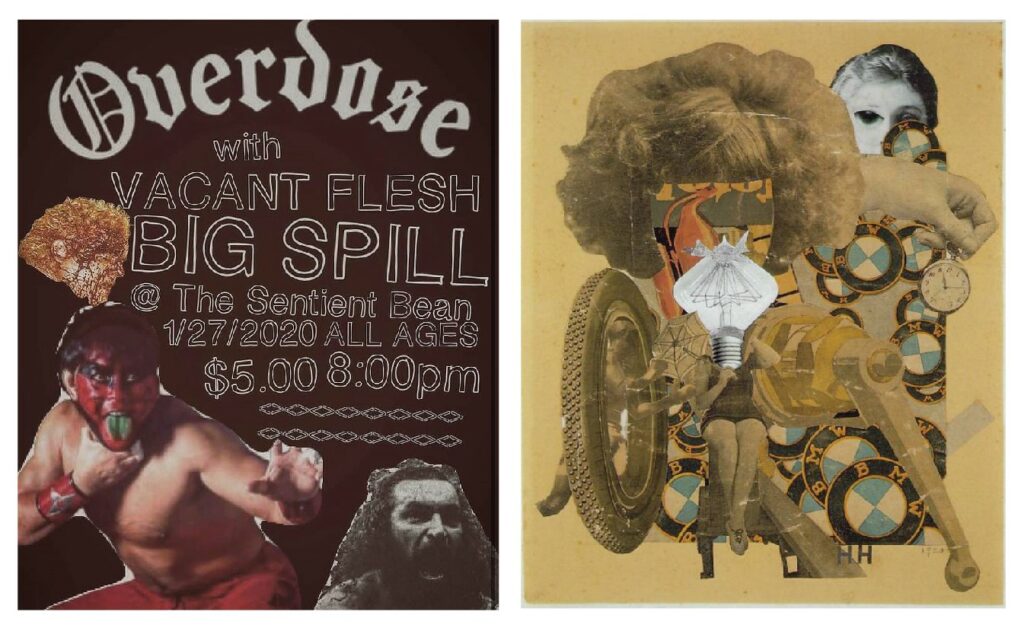

Surprisingly none of the local metal shows made the list.

Not even when “Vacant Flesh” is playing with “Overdose” for only 5 bucks!”

Although this isn’t surprising seeing as Savannah loves to keep up appearances as a quaint, historic posh little southern experience, it does oversimplify the “mood” of the city. What appears at first glance to be touristy and unassuming, is actually a hotbed for angry youth driven Southern metal. With the presence of SCAD, the alternative and dark history and the layout of the city, Savannah allows the local metalhead skaters to act as modern day flaneurs, reflecting, for better or for worse, a kind of modernism thriving in the squares.

WHY METAL?

Savannah’s metal scene is a reflection of modernist ideas in that the city can be viewed through the skateboarding metalhead eyes of a teenager, but metal in general has its own modernist strings.

With early rumblings in the 1950s, heavy metal really began with the British band Black Sabbath’s first album in 1968. Immediately the band was steeped in socially taboo subjects such as “political corruption”, “recreational drug use” and “social ostracization.” The genre soon grew more popular with bands like “Deep Purple” and “Iron Maiden” screaming away about modernistic themes, although in a different time, these lyrics and topics are reflective of unrest and reactions to industrialization.

After a slight downturn in popularity, with grunge and alternative rock seeing more attention, metal has had recent resurges with youth, “Symphonic” and “In Flames” are some of many popular bands in the scene trying new “avant-garde” styles that resonate with die hard fans. These “new” ideas also reflect the modernist aspects of metal as they can be compared to the desire for new literary styles and pieces.

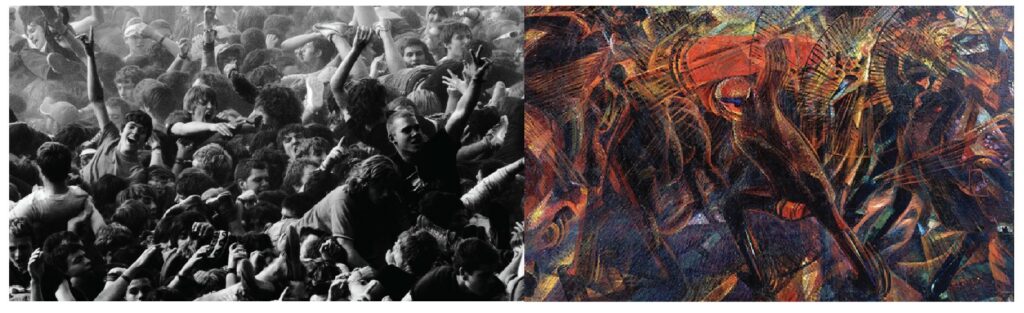

There is then the specifics of Southern Metal, a synthesis of different genres, as Michael Mcdowell puts it in his dissertation regarding the southern metal scene, “Southern Metal music is an outgrowth of Black Sabbath-influenced metal, Black Flag influenced hardcore punk, Lynyrd Skynyrd-influenced Southern rock, and Melvins-influenced “sludge.” This blend of “traditional” and “new” is also a comparison to the modernist era, with different “isms” and ideals spread out, in fierce opposition at times, within the whole of the movement. This is especially reflective in Savannah. Savannah’s mood is a dichotomy, — seen most clearly in its metal scene– a constant struggle between the youth crying for “new” and the defiant foot of tradition.

WHY SKATING?

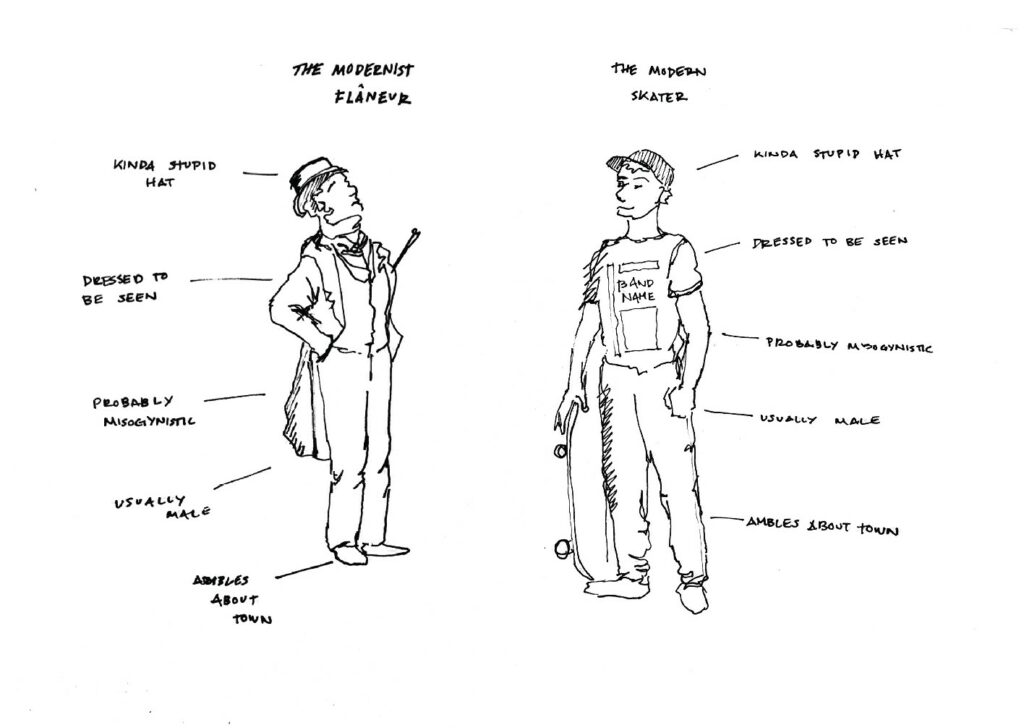

Metal is inherently connected with the “fringe” of society that often picks up a skateboard. The two seem to coalesce is Savannah with the true flaneur of the city being not the fancily clad horse carriage riding tourist, but the band t-shirt wearing skater kid.

When Savannah was laid out by Oglethorpe in 1733, it was constructed with the intention of walking. The squares are set up parallel to large main streets in rows that allow pedestrians to wind around the historic buildings and green patches. This aspect also allows skateboarders to roam with the fear of cars being lessened. This leads to a sort of meandering about the city on four wheeled pieces of wood, for no particular purpose but to be moving with the group, and of course to be seen.

This is flaneur behavior.

In the same way that London lent to the strolling fashionable man about town, Savannah’s metal scene, its winding squares and its populous of “onlookers” lends itself to the teenage skater.

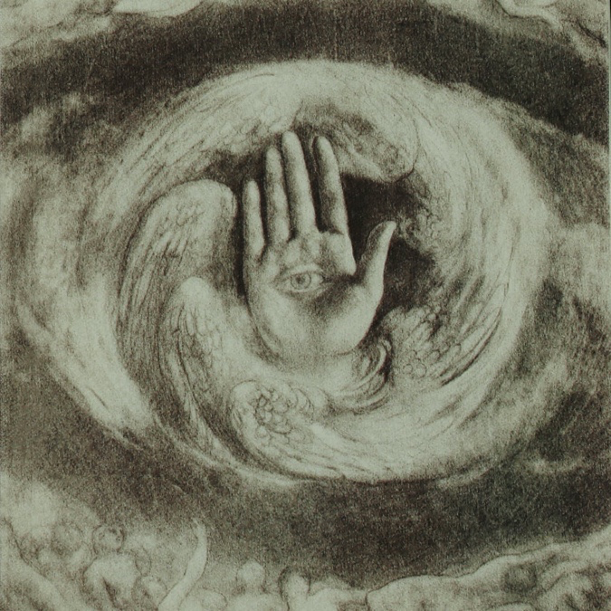

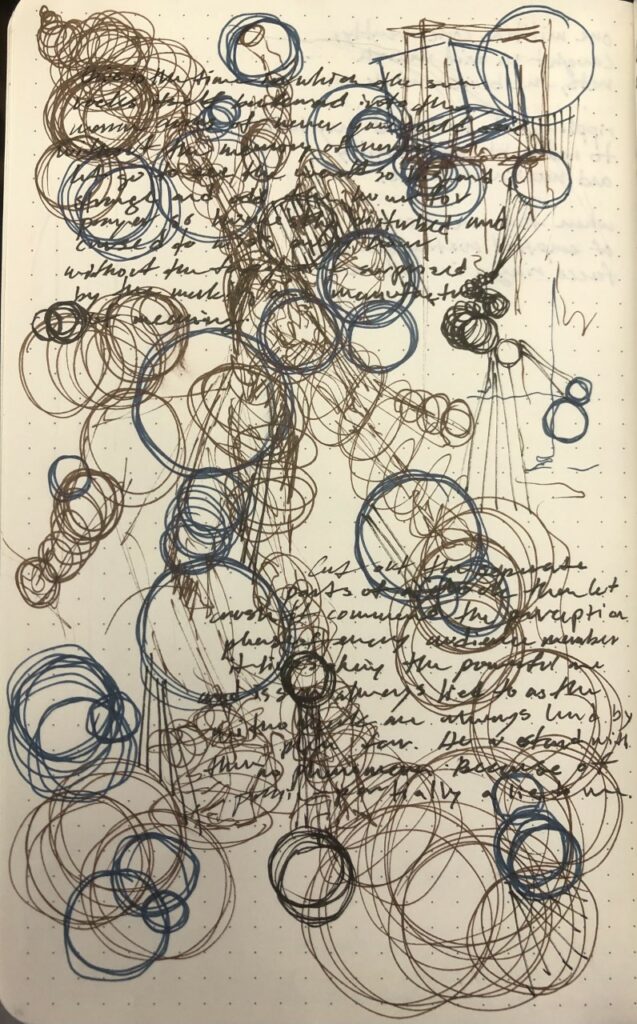

In my created image above I point out some less positive aspects of the flaneur and how these are also reflected in the “modern skater” I reference the “probably misogynistic” qualities and the male privilege they represent as they can walk around the city with little to no worry. The irony of the Savannah skater is that they may listen to Black Sabbath scream about social unrest with teary eyes, yet perpetuate the social chains of their own city by remaining ignorant or participating in sexism, homophobia, racism and xenophobia.

This begins to tap into another aspect that is so central to the “mood” or “core” of Savannah and the Savannah metal scene, the balance of tradition and progress, politically and socially.

WHY SAVANNAH?

Southern metal consists mostly of white, working class musicians. Savannah is no exception, yet certain aspects of Savannah’s culture and mood allow it to extend past this one dimension and diversify and grapple with this aspect of the scene in many ways.

Savannah has its pearly exterior, from the park benches to Spanish moss in the trees, Savannah reeks of kitschy southern performance. But Savannah also has rich history in alternative forms of expressions, from housing some of the first successful drag queens to jazz musicians, filmmakers and now artists from all over the world. Savannah has a long history of being much more akin to New Orleans when the sun goes down than those coaxing families toward their waterfront hotels would like you to believe.

Savannah is home of course to SCAD, the Savannah College of Art and Design, which adds to this tension as it brings students from all over the world eager to see live music and bring their own unique perspectives to the scene. SCAD, being an art school also naturally fuels the anti-establishment feelings with its students, who tend to lean toward fringe activities such as skateboarding and metal. But, this is where Savannah is truly found, there is a creation of something new (how modernist) in Savannah’s scene specifically. The diversity of the SCAD students mixed with the traditional ideals of both what is southern and what is metal meld into a fierce amalgamation of youth.

Savannah’s unique local businesses also lend to this synthesis, as cafes and boutique stores open their doors after hours to house gigs and all types of performances. These places seem to understand the line they walk, holding poetry readings and metal shows within the same day.

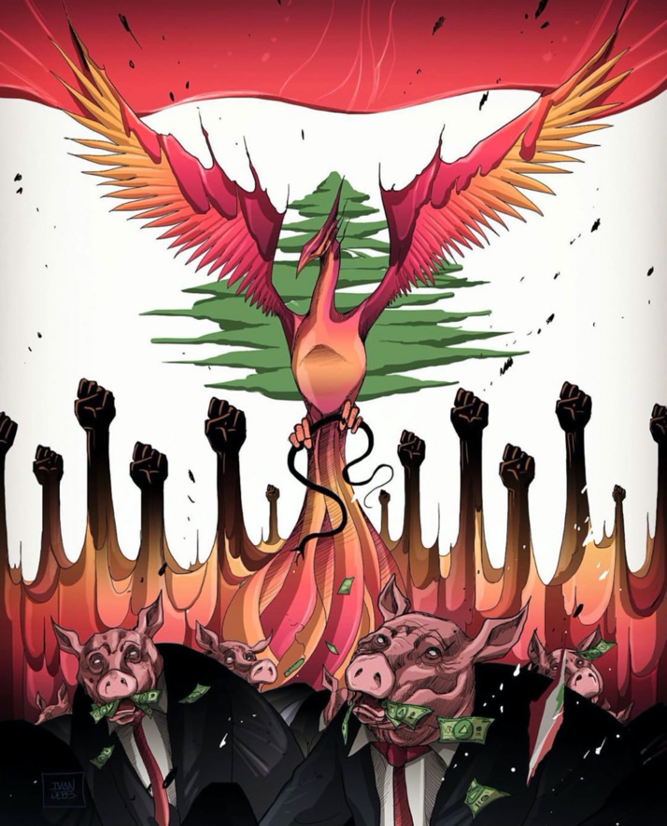

This allows for the true growth of Savannah, real southern charm to shine through. When old white men who have listened to metal for decades begrudgingly nod to the screaming “newness” of young college students from quite literally all over the world, something signifigant occurs. There is an evolution from the old metal that concerns industrialization and new metal that concerns gender non comformace and racial injustice.

This is not to say Savannah nor its metal scene is without prejudice, in fact as mentioned before “the Flanuers” still can promote ignorance and the ugly horns of deep seeded racism still protrude with the influence of “Lynryd Skynrd” and southern tradition. But the majority of youth in the scene are actively fighting against this, far more than those who wish to keep Savannah’s image fountains and feathers.

A new band called “Pig Teeth” and “Basically Nancy” have become more popular in the metal scene both consisting of all female musicians. Recent protests were supported and even organized and spread by bands in the Savannah scene, and those that have not shown support have been shunned and boycotted by local business.

Savannahs metal scene colors the mood of Savannah for me, it demonstrates clearly the strange line Savannah walks between quaint Southern town and screaming hotbed of avant-garde art and music.

SOURCES:

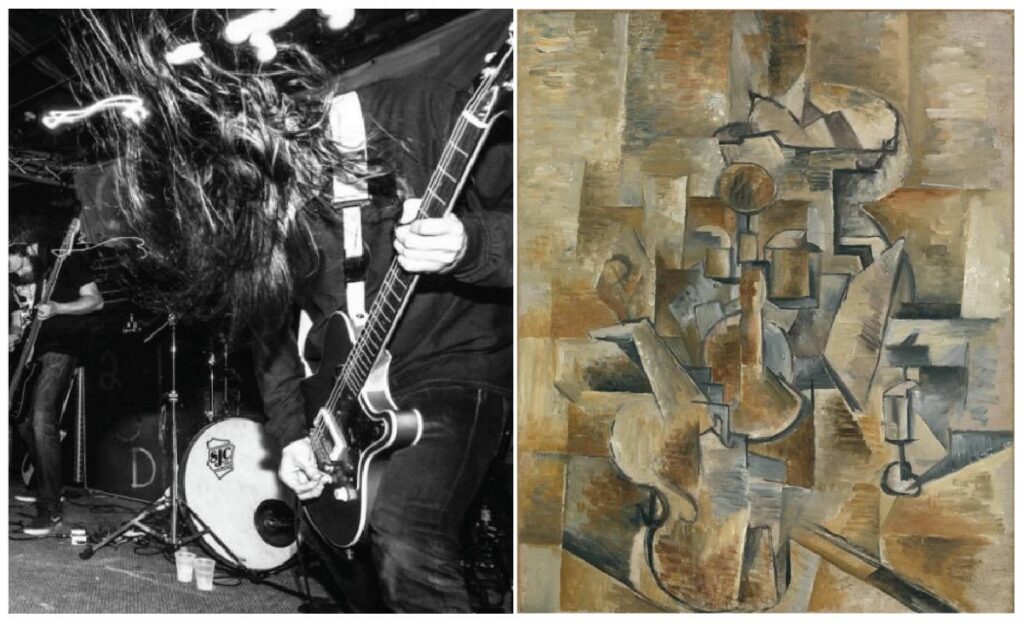

Danae. “Digital Montage: On Collage and the Legacy of Modernism.” Medium, DIGITAL ART WEEKLY, 13 Jan. 2020, medium.com/digital-art-weekly/digital-montage-on-collage-and-the-legacy-of-modernism-ac9043247c61.

McDowell, Micheal. Southern Performance and the Southern Metal Scene. scholarcommons.usf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=7515&context=etd.

Carrà, Carlo. “Carlo Carrà. Funeral of the Anarchist Galli. 1910-11: MoMA.” The Museum of Modern Art, www.moma.org/collection/works/79225.

“Heavy Metal 101 @ MIT.” A Brief History of Metal | Heavy Metal 101 @ MIT, metal.mit.edu/brief-history-metal.

28 Feb, 2021, and 2021 27 Feb. “The Origins of Metal and How It Found Its Place in the Music Industry.” Young Post, www.scmp.com/yp/discover/entertainment/music/article/3072431/origins-metal-and-how-it-found-its-place-music.

“Eagles of Death Metal.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 1 Mar. 2021, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eagles_of_Death_Metal.